Fourth Wave Feminism: Why No One Escapes

Today’s outsized Femocracy is more desperate and (self) destructive than its successful progenitors

JOANNA WILLIAMS

Feminism, in its second wave, women’s liberation movement guise, has passed its first half century. And what a success it has been! Betty Friedan’s frustrated housewife, bored with plumping pillows and making peanut butter sandwiches, is now a rarity. We might still be waiting for the first female president, but women—specifically feminists—are now in positions of power across the whole of society.

Yet feminism shows no sign of taking early retirement and bowing out, job done. Instead, it continues to  reinvent itself. #MeToo is the cause du jour of fourth-wave feminism but, disturbingly, it seems to be taking us further from liberation and pushing us towards an increasingly illiberal and authoritarian future. It’s time to take stock.

reinvent itself. #MeToo is the cause du jour of fourth-wave feminism but, disturbingly, it seems to be taking us further from liberation and pushing us towards an increasingly illiberal and authoritarian future. It’s time to take stock.

Over the past five decades, women have taken public life by storm. When it comes to education, employment, and pay, women are not just doing better than ever before—they are often doing better than men, too. For over a quarter of a century, girls have outperformed boys at school. Over 60 percent of all bachelor’s degrees are awarded to women. More women than men continue to graduate school and more doctorates are awarded to women. And their successes don’t stop when they leave education behind. Since the 1970s, there has been a marked increase in the number of women in employment and many are taking managerial and professional positions. Women now comprise just over half of those employed in management, professional, and related occupations.

Women aren’t just working more, they are being paid more. Women today earn more in total than at any other point in time, and they also earn more as a proportion of men’s earnings. For younger women in particular, the gender pay gap is narrowing. Between 1980 and 2012, wages for men aged 25 to 34 fell 20 percent while over the same period women’s pay rose by 13 percent. Some data sets now suggest that women in their twenties earn more than men the same age. Although high-profile equal pay campaigns appear to suggest otherwise, when we compare the pay of men and women employed in the same jobs and working for the same number of hours each week, the gender pay gap all but disappears. Four out of every 10 women are now either the sole or primary family earner—a figure which has quadrupled since 1960.

But this is not just about the lives of women: it is feminism as an ideology that has been incredibly successful. For over four decades, feminist theory has shaped people’s lives. Making sense of the world through the prism of gender and seeking to root out sexual inequality is now the driving force behind much that goes on in the public sphere.

Back in 1986, in one of the first examples of new legislation explicitly backed by feminists, the Supreme Court ruled that sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination. This has had a profound impact upon all aspects of employment legislation. As a result, a layer of managers and administrators, sometimes referred to as “femocrats,” are employed to oversee sexual equality and manage sexual harassment complaints in workplaces and schools.

Elsewhere, the influence of feminism can be seen in the expansion of existing laws. When Title IX of the Education Amendments was passed in 1972, it was designed to protect people from discrimination based on sex in education programs that received federal funding. It was a significant—and reasonably straightforward—piece of legislation introduced at a time when women were underrepresented in higher education. It first began to take on greater significance following a 1977 case led by the feminist lawyer and academic Catharine MacKinnon in which a federal court found that colleges could be liable under Title IX not just for acts of discrimination but also for not responding to allegations of sexual harassment.

Not surprisingly, definitions of sexual harassment began to expand in the late 1970s. In education, the term came to encompass a “hostile environment” in which women felt uncomfortable because of their sex. By this measure, sexual harassment can occur unintentionally and with no specific target. Furthermore, a hostile environment might be created by students themselves irrespective of the actions of an institution’s staff. As a result, colleges became responsible for policing the sexual behavior of their students too.

Pressing forward under the Obama administration, sexual misconduct cases on campuses were tried under a preponderance of the evidence standard rather than a higher standard of clear and convincing evidence. Within these extrajudicial tribunals, students—most often young men—could be found guilty of sexual assault or rape and expelled following unsubstantiated allegations and with little opportunity to defend themselves. Although current Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has revoked the Obama-era guidelines that instituted these kangaroo courts, many institutions under pressure to react have expanded their zero tolerance policies, often at the expense of basic due process and fairness.

In the 1970s, radical feminists opposed the Equal Rights Amendment, arguing that it individualized and deradicalized feminism. “We will not be appeased,” they asserted. “Our demands can only be met by a total transformation of society, which you cannot legislate, you cannot co-opt, you cannot control.”

Yet today, a feminist outlook now shapes policy, practice, and law at all levels of the government, as feminists seek to transform society through the state rather than by opposing it. Most recently this has taken form in the demand for affirmative consent, or “yes means yes,” to be the standard in rape cases. This places the onus on the accused to prove they had sought and obtained consent; in other words, they must prove their innocence.

This is a radical shift, yet it is being enshrined in legislation with little discussion. California and New York have passed legislation requiring colleges to adopt an affirmative consent standard in their sexual assault policies. In 2016, the American Law Institute, influential with state legislators, debated introducing an affirmative consent standard into state laws. The proposal was ultimately rejected but the fact that it was even taken seriously shows feminism’s growing legal influence.

History tells us that legislation driven by feminism can have unintended consequences. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), passed in 1994 as part of President Clinton’s massive $30 billion crime bill, aimed to put 100,000 police officers on the street and funded $9.7 billion for prisons. VAWA sought more prosecutions and harsher sentences for abuse in relationships. But a more intensive law enforcement focus on minority communities, coupled with mandatory arrests of both partners on the scene of a dispute, resulted in unanticipated blowback. Police were accused of over-criminalizing minority neighborhoods; critics said women were disinclined to call the police for fear of being arrested themselves. A 2007 Harvard study suggests that mandatory arrest laws may have actually increased intimate partner homicides and, separately, women of color have described violence at the hands of the arresting police officers.

Ultimately, the crime bill merely punished; it didn’t help prevent domestic abuse against women.

* * * * * *

Although all women have in some way benefited from feminism’s decades-long campaign against inequality, it is clear that some—namely middle- and upper-class college graduates—have been more advantaged than the rest. Feminists in the 1960s argued that all women had interests in common; they shared an experience of oppression. The same can hardly be said today. An elite group of women with professional careers and high salaries has little in common with women juggling two or more jobs just to make ends meet. Yet the feminist voices that are heard most loudly continue to be those of privileged women.

High-profile feminists like Anne-Marie Slaughter, the first woman director of policy planning at the State Department, and Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, sell books and make headlines for criticizing family-unfriendly employment practices and the gender pay gap. Good for them! But remember that these women have incomes and lifestyles that put them in a different league from the vast majority of women—and men. They identify more closely with the tiny proportion of male CEOs than they do with women who have jobs rather than careers, who wear uniforms rather than dry-clean-only suits to work, who have no time to hit the gym before heading to the office. Their push for “lean-in” circles appeals more to young college grads than women struggling just to put food on the table. Their vociferous feminist call to arms falls flat in Middle America—yet we are told they speak for all women.

In 2018, feminists do walk the corridors of power. But in order to maintain their position and moral high ground, they must deny the very power they command. For this reason, feminism can never admit its successes—to do so would require its adherents to ask whether their job is done. For professional feminists, women who have forged their careers in the femocracy, admitting this not only puts their livelihoods at risk, but poses an existential threat to their sense of self. As a result, the better women’s lives become, the harder feminists must work to seek out new realms of disadvantage.

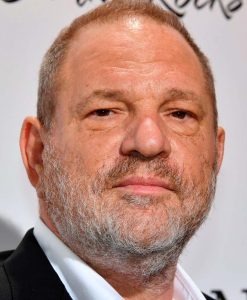

The need to sustain a narrative of oppression explains the continued popularity of the #MeToo phenomenon. In October 2017, The New York Times ran a story alleging that Hollywood  producer Harvey Weinstein, who had the power to make and break careers, had committed a number of serious sexual offenses. (The allegations against Weinstein mounted and he is now being charged with sexual assault and rape.) Over the following weeks and months, accusations of sexual misconduct were leveled against a host of other men in the public eye.

producer Harvey Weinstein, who had the power to make and break careers, had committed a number of serious sexual offenses. (The allegations against Weinstein mounted and he is now being charged with sexual assault and rape.) Over the following weeks and months, accusations of sexual misconduct were leveled against a host of other men in the public eye.

Such serious accusations need to be dealt with in the courts and, if found guilty, the perpetrators punished accordingly. But rather than arrests, trials, and criminal proceedings, #MeToo has gathered pace through social media. Actress Alyssa Milano took to Twitter on October 18 and asked women who had been sexually harassed or assaulted to “write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” Thousands of women came forward to call out their own abusers or simply to add their names to a growing list of victims. #MeToo took on a life of its own; it readily lent itself to an already-established fourth-wave feminist narrative that saw women as victims of male violence and sexual entitlement.

Women in the public eye are now routinely asked about their own experiences of sexual harassment. Some have publicly named and shamed men they accuse of sexual assault or, as with the case of comedian Aziz Ansari, what can perhaps best be described as “ungentlemanly conduct.” Others are more vague and suggest they have experienced sexual harassment in more general terms. What no woman can do—at least not without instigating a barrage of criticism—is deny that sexual harassment is a major problem today.

The success of #MeToo is less about real justice than the common experience of suffering and validation. It is a perfect social media vehicle to drive the fourth-wave agenda into another generation. Hollywood stars and baristas may have little in common but all women can lay claim to having experienced male violence and sexual harassment—or, failing that, potentially experiencing abuse at some indeterminate point in the future. Statistics on domestic violence, rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment are used to shore up the narrative that women, as a class, suffer at the hands of men.

But scratch the surface and often these statistics are questionable. In recent years, at the hands of femocrats, definitions of violence and sexual harassment have been expanded. On campus, all kinds of behaviors, from touching through clothes to non-consensual sex, are grouped together to prove the existence of a rape culture. When sexual harassment is redefined as unwanted behavior, it can encompass anything from winking, to whistling, to staring, to catcalling. There is little objectively wrong with the action—it is simply the fact that it is unwanted that makes it abusive. Today, we are encouraged to see violence, especially violence against women and girls, everywhere: in words that wound, personified in a boorish president, in our economic and legal systems. This is violence as metaphor rather than violence as a physical blow. Yet it is a metaphor that serves a powerful purpose—allowing all women to share in a common experience of victimhood, and, as such, justifying the continued need for elite feminism.

Problems with #MeToo are too rarely discussed. Violence and sexual assaults do occur, but these serious crimes are trivialized by being presented as on a continuum with the metaphorical abuse. The constant reiteration that women are victims and men are violent perpetrators does not, in itself, make it true. It pits men and women against each other and, in the process, infantilizes women and makes them fearful of the world. It also masks a far more positive story: rates of domestic violence have been falling. Between 1994 and 2011, the rates of serious intimate partner violence perpetrated against women—defined as rape, sexual assault, robbery, or aggravated assault—fell 72 percent.

The consequences of entrenching in law assumptions that women are destined to become victims of male violence and harassment are dangerously authoritarian. Feminists now look not to their own resources, or to their family and friends, but to the state to protect them. Black men in particular can find themselves disproportionately targeted by feminist-backed drives for legal retribution. A 2017 report from the National Registry of Exonerations suggests that black men serving time for sexual assault are three-and-a-half times more likely to be innocent than white defendants who have been convicted of the same crime.

In the meantime, demands for the punishment of bad behavior are inevitable. Male catcalling in the UK and France could soon be a criminal offense. While similar bans have been unsuccessful in the U.S., there are plenty of street harassment laws at the state level that feminists could co-opt if necessary. Additionally in England, there are proposals to criminalize “upskirting” or taking a photograph up a woman’s skirt. Upskirting is a vile invasion of a person’s privacy. However, the majority of instances are covered under existing indecency and voyeurism laws. The proposal, as with others, is a feminist signaling device: the message is, yet again, that the world is a hostile place for women and their only course of action is to seek redress from the state.

Meanwhile, working-class women are effectively exploited as a voiceless stage presence, brought on when convenient to shore up the authority of the professional feminist. On occasion this means the livelihoods of regular women are placed in jeopardy for the greater good of the collective. Earlier this year, a group of A-list Hollywood actresses petitioned against tipping waitresses in New York restaurants, arguing it was exploitive and encouraged sexual harassment. Perhaps unsurprisingly, servers shot back that they would like to continue receiving tips, thank you very much.

* * * * * * *

Fourth-wave feminism is increasingly authoritarian and illiberal, impacting speech and behavior for men and women. Campaigns around “rape culture” and #MeToo police women just as much as men, telling them how to talk about these issues. When The Handmaid’s Tale author Margaret Atwood had the effrontery to advocate for due process for men accused of sex crimes, her normally adoring feminist fans turned on her. She referred to it in a Globe and Mail essay in January entitled “Am I a Bad Feminist?”

“In times of extremes, extremists win,” she wrote. “Their ideology becomes a religion, anyone who doesn’t puppet their views is seen as an apostate, a heretic or a traitor, and moderates in the middle are annihilated.”

The fact is, men are publicly shamed every day, their livelihoods and reputations teetering on destruction, before they even enter a courtroom.

Frankly, it is disastrous for young women to be taught to see themselves as disadvantaged and vulnerable in a way that bears no relationship to reality. Whereas a previous generation of feminists fought against chaperones and curfews, today’s #MeToo movement rehabilitates the argument that women need to be better protected from rapacious men, or need “safe spaces.” Women come to believe that they will be harassed walking down the street, that they will be paid less than men for the same work, and that the world is set against them. The danger is that, rather than competing with men as equals, women will be so overwhelmed by the apparent size of the struggle that they will abandon all efforts and call upon external helpmates, like the state and ugly identity politics that push good men away. Women’s disadvantage thus become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

All the while, the real problems experienced by many American women—and men—such as working long hours for a low wage and struggling to pay for child and healthcare costs, are overlooked.

When second-wave feminism burst onto the scene more than 50 years ago it was known as the women’s liberation movement. It celebrated equality and powerfully proclaimed that women were capable of doing everything men did. Today, this spirit of liberation has been exchanged for an increasingly authoritarian and illiberal victim feminism. With every victory, feminism needs to reassert increasingly spurious claims that women are oppressed. For women and men to be free today, we need to bring back the spirit of the women’s liberation movement. Only now it’s feminism from which women need liberating.

************

Original article

ER recommends other articles by Strategic Culture Foundation