Why is Nobody Talking about the Union for the Mediterranean?

- EU countries involved in the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) appear unbothered by promoting “integration” — or even claiming “a common heritage” — with countries such as Mauritania, where, according to recent reports, up to 20% of the population (Haratines and other Afro-Mauritanian groups) is enslaved, and anti-slavery activists are regularly tortured and detained.

- There is not the slightest allusion in the UfM yearly report, or in the 2017 Roadmap for Action, to the fact that in most Muslim countries, sharia law influences the legal code — especially regarding marriage, divorce, inheritance and child custody — and that gender inequality may therefore be institutionalized and not something likely to change, regardless of the number of UfM projects.

- Given these large sums of money involved, it is remarkable that the UfM and its activities enjoy little to no scrutiny in the European press.

In July, the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) celebrated its 10-year anniversary. Most Europeans, however, are unlikely to have heard about the Union, let alone the anniversary. The media rarely reports on the UfM and its activities.

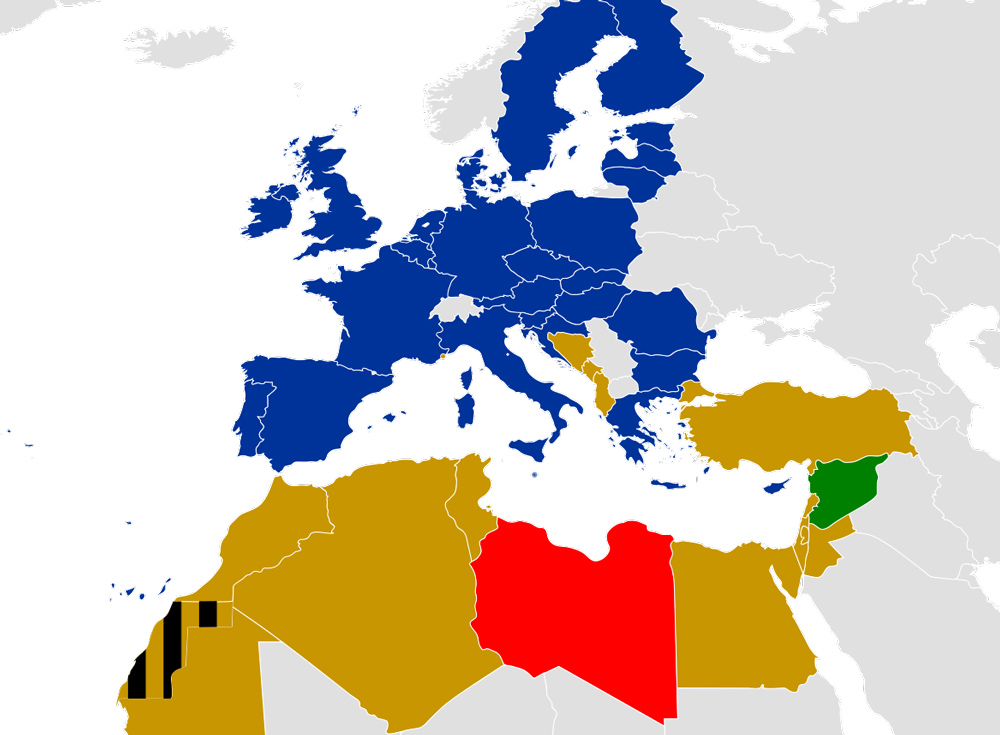

The participating countries in the UfM are the 28 European Union (EU) member states and the Southern Mediterranean countries, which include Albania, Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, “Palestine”, Syria (temporarily suspended), Tunisia and Turkey. Libya has observer status in the UfM. The UfM is chairedby a “co-presidency” shared between the European Union and Jordan. The UfM Secretariat maintains the daily operations of the UfM and is run by a Secretary General, presently Nasser Kamel (Egypt).

The UfM was launched by a decision of the UfM Heads of State and Government in Paris in July 2008, and constitutes an institutionalization of the Barcelona Process, which began in November 1995 with the signing of the Barcelona Declaration.

According to the European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMed), the Euro-Mediterranean alliance launched by the Barcelona Declaration Process “was structured around three main work areas (political and security dialogue; economic and financial partnership; and social, cultural and human partnership)” between the EU and the mainly Muslim majority countries in North Africa and the Middle East (usually referred to in UfM context as the Southern Mediterranean).

In January 2017, the 43 foreign ministers of the UfM agreed on a “Roadmap for Action” in Barcelona, which aims at “enhanced regional cooperation and integration in the Mediterranean,” setting out “three key interrelated priorities, regional stability, human development and integration.” It was the first political document adopted by the UfM foreign ministers since 2008.

The UfM lists a number of ways in which it seeks to achieve regional stability and human development. One of them is “Intercultural and Interfaith dialogue” the aim of which is, among other things:

“[T]o exert all efforts to bridge any potential cultural divide to fight against extremism and all forms of racism and to build upon a common heritage and aspirations. Intercultural and Interfaith dialogue in the Mediterranean is an important underlying dimension of all regional cooperation activities in the framework of the UfM.” [1]

The EU countries involved in the UfM appear unbothered by promoting “integration” — or even claiming “a common heritage” — with countries such as Mauritania, where, according to recent reports, up to 20% of the population (Haratines and other Afro-Mauritanian groups) is enslaved, and anti-slavery activists are regularly tortured and detained.

The UfM has held 15 ministerial conferences on “key strategic areas” in the past 5 years on topics such as Strengthening the role of Women in Society (Egypt, November 2017), Sustainable Urban Development (Egypt, May 2017), Water (Malta, April 2017), Energy (Italy, December 2016) Employment and Labour (Jordan, September 2016), Regional Cooperation and Planning (Jordan, June 2016), Blue Economy (Belgium, November 2015) Digital Economy (Belgium, September 2014), Environment and Climate Change (Greece, May 2014), Industrial Cooperation, (Belgium, February 2014) Energy (Belgium, December 2013), and Transport (Belgium, November 2013), as well as two Foreign Minister Conferences (Spain January 2017 and Spain November 2015). [2]

The UfM aims to reach its priorities through projects such as “Empowering women and youth in the Mediterranean”, “Promoting job creation and inclusive growth” and “Enhancing the Role of Women and Youth in Preventing Violent Extremism.” [3]

There is not the slightest allusion in the yearly report, nor in the 2017 Roadmap for Action, to the fact that in most Muslim countries, sharia law influences the legal code — especially regarding personal status law, which concerns marriage, divorce, inheritance and child custody — and that gender inequality may therefore be institutionalized and not something likely to change, regardless of the number of UfM projects. Nor is there any allusion to the role of Islamism in fostering “violent extremism“. Instead, the roadmap for action speaks of joining “regional and international efforts to address socio-economic root causes of terrorism and extremism” and “developing further projects and initiatives of high impact, with a special focus on youth employability and women empowerment.” [4]

According to the European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMed):

“From 1995 to 2006, the EU allocated 16,000 million euros through MEDA programmes for bilateral and regional cooperation, aimed at fostering both socioeconomic projects (modernisation of the industry, promotion of the private sector, reform of the health sector, development funds…) and political and good governance reforms…

“The cooperation funds are channelled through the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), aimed at both the eastern European and southern Mediterranean neighbourhood. The joint budget for both regions for the period 2007-2013 amounts to 11,000 million euros...

The funds allocated to cooperation with the EU neighbouring countries (in eastern Europe and the southern Mediterranean) for the period 2014-2020 amount to 15,000 million euros.”

These figures do not include bilateral agreements between the UfM and EU countries, such as the €6.5 million multi-annual financing agreement between the UfM Secretariat and Sweden “to deepen and amplify UfM specific cooperation initiatives and core activities promoting regional dialogue.”

Given these large sums, it is remarkable that the UfM and its activities enjoy little to no scrutiny in the European press. Especially as, in the words of IEMed in its 2015 assessment of the 20th anniversary of the Barcelona Process, “The scenario of concord set out for the Mediterranean in the 1995 Barcelona Declaration has never become a reality”.

Subsequent Islamic radicalization and terrorism and the years-long migrant crisis constitute recent examples of the failure. IEMed’s assessment continues:

“The roadmap designed in the Catalan capital could not predict the destabilising effects on the region of al-Qaeda on 11S and the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq; the political immobility and lack of reforms and improvements in governance in many MPCs; the non-creation of the free trade area in the Mediterranean scheduled for 2010; the lack of south-south regional integration; the instability caused by the Arab Spring since 2011, currently with two failed states, Syria and Libya; the migration and refugee crises; or the emergence of Islamic State terrorism that is ravaging Syria and Iran and has already shown its capacity to attack Europe.”

The UfM has itself conceded:

“UfM countries have among the highest unemployment rates in the world, affecting mostly youth and women, which adds to many other pressing issues such as social cohesion, migration or efforts to counter radicalization.” [5]

Despite this apparent evidence of the failure of the Barcelona Process and the UfM, the latter nevertheless sees itself as having “entered a new phase, building on the progress achieved so far… increasing and expanding activities demonstrate that windows of opportunity exist to further develop regional cooperation.” [6]

The UfM, undeterred, barrels on with its goal to achieve:

“greater levels of integration and cooperation in the region through a specific methodology that has yielded positive results in terms of political dialogue and the implementation of region-wide initiatives in which young people play a key role.

With more than 50 labelled projects and over 300 ministerial and expert fora gathering 25,000 stakeholders since 2012, UfM activities illustrate the strong belief that regional challenges call for regional solutions and that there is no security without development.”

It seems counterintuitive that nearly a quarter century of costly investment by Europe in the southern UfM countries appears to have yielded few to no positive results. Despite the UfM’s own aforementioned assessment of challenges having reached “unprecedented levels,” the EU nevertheless continues the Barcelona Process in the form of the UfM. It is also bizarre that any substantive evaluation of the costs and benefits of the Barcelona Process, and the UfM and its many projects is absent from most public discourse, as the media apparently fail to report on the UfM and its activities.

A map of the Union for the Mediterranean members. Blue are EU member states, brown are other members, Libya (red) is an official observer, and Syria (green) is a suspended member. (Image source: Treehill/Wikimedia Commons) A map of the Union for the Mediterranean members. Blue are EU member states, brown are other members, Libya (red) is an official observer, and Syria (green) is a suspended member. (Image source: Treehill/Wikimedia Commons) |

Judith Bergman is a columnist, lawyer and political analyst.

[1] UfM Roadmap for Action 2017, p 12.

[2] UfM annual Report 2017, p 9.

[3] Ibid. p15 ff.

[4] UfM Roadmap for Action 2017, p 14.

[5] UfM annual Report 2017, p 15.

[6] Ibid p 10.

Original article

ER recommends other articles by The Gatestone Institute