By Ryan McMaken

That didn’t take long. Only hours after the final results came in for a British exit from the EU, political leaders in Scotland are talking about renewing their drive to secede from the United Kingdom.

Pointing to the fact that a large majority of Scots voted to remain in the EU, Scottish advocates for independence are now claiming (convincingly) that Scotland is leaving the EU against its will.

Many of us who advocated for Scottish secession in 2014 were, of course fine with Scottish secession at the time. And we’re still fine with it now. Scotland should be free to say good bye and go its own way.

Some opponents of Scottish exit, however, have claimed that Scotland is too small “to go it alone.” Defenders of Scottish independence call this the “too wee, too poor, too stupid” argument.

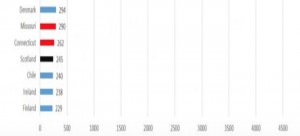

Even the most rudimentary analysis, however, shows that size is not an issue for Scotland. With an official GDP of approximately 245 billion, Scotland is not too much different from Ireland, Finland, and Denmark. Its economy is much larger than that of Iceland (16.7 bln) and New Zealand (172 bln).

With a population of 5.3 million, this puts Scotland either similar to or larger than Denmark, Norway, Finland, New Zealand, and Ireland.

With a population this size, Scotland’s GDP per capita comes out to around $45,000 which naturally is similar to the UK overall today, and also similar to Canada, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, and a number of other European states, both large and small.

Some will argue that Scots cannot go it alone because they rely too much on English taxpayers for transfer payments such as pensions. This is no doubt partially true, although the UK government also extracts tax dollars from Scots, regulates Scottish trade with the EU and everyone else, and perhaps the Scottish simply want independence even if it means a temporary disruption in living standards.

Overall, though, there’s no denying that Scotland even by itself is well within the realm of ordinary wealthy nation states, in terms of population, and the size of its economy. Scotland is in no way an outlier.

The claim that it is “too small” was repeated today, however, in this article by Roger Bootle at The Telegraph in which he writes:

Believe it or not, there is an extensive economic literature on the subject of the optimum size of a country, or more accurately, political association. From the economic point of view, as the size of political entities gets larger, there is scope for economies of scale in government and the provision of public goods such as defence. Equally, within a single political entity there are no restrictions on trade, such as tariffs or quotas so, other things being equal, the gains from trade are maximised as political entities grow larger.

Yet there are limits to the desirable size of political entities, such that, as things stand anyway, a single world government would not be optimal. The larger, and certainly the more heterogeneous, a political entity is, the more resources are taken up with arguing about distribution, that is to say who should benefit from various sorts of public expenditure, and who should pay for it. The quality of government tends to deteriorate.

Bootle is correct that there are certainly advantages of size when it comes to national defense. Obviously, it’s much harder for a foreign invader to overrun Russia than Poland. What Bootle misses, however, is that these issues can be addressed through confederation rather than through political unification. The original purpose of the United States, of course, was to act as a confederation for purposes of national defense. Member, states, however, remained autonomous within their own borders. Similar structures have existed throughout history, from NATO to the Hanseatic league of northern Europe.

Scotland need not be part of the UK to enter into a defense agreement with the British.

The rest of Bootle’s argument appears even more specious. It is not a given, for example, that larger states facilitate trade. As the UK experience has shown, membership in the EU has granted access to some markets, but it has cut off access and flexibility with other markets. (Norway and Switzerland have access to these same markets, by the way, without EU membership.)

This was also an enormous issue and source of conflict in the United States, in regards to southern states. Yes, membership in the United States facilitated trade among states, but trade between Southern states and foreign markets was hampered by US tariff policy. To claim that gains from trade are “maximised” by larger states is rather overstating it, to say the least.

In fact, there are many reasons to believe that the “optimal” size of state is considerably smaller than what Bootle suggests it is. (The subtext of Bootle’s article, of course, is that Scotland is below the optimal size.)

As Peter St. Onge wrote in 2014 about the Scottish referendum at the time:

So small is possible. But is it a good idea?

The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is resoundingly “Yes!” Statistically speaking, at least. Why? Because according to numbers from the World Bank Development Indicators, among the 45 sovereign countries in Europe, small countries are nearly twice as wealthy as large countries. The gap between biggest-10 and smallest-10 ranges between 84 percent (for all of Europe) to 79 percent (for only Western Europe).

This is a huge difference: To put it in perspective, even a 79 percent change in wealth is about the gap between Russia and Denmark. That’s massive considering the historical and cultural similarities especially within Western Europe.

Even among linguistic siblings the differences are stark: Germany is poorer than the small German-speaking states (Switzerland, Austria, Luxembourg, and Liechtenstein), France is poorer than the small French-speaking states (Belgium, Andorra, Luxembourg, and Switzerland again and, of course, Monaco). Even Ireland, for centuries ravaged by the warmongering English, is today richer than their former masters in the United Kingdom, a country fifteen times larger.

Why would this be? There are two reasons. First, smaller countries are often more responsive to their people. The smaller the country the stronger the policy feedback loop. Meaning truly awful ideas tend to get corrected earlier. Had Mao Tse Tung been working with an apartment complex instead of a country of nearly a billion-people, his wacky ideas wouldn’t have killed millions.

Second, small countries just don’t have the money to engage in truly crazy ideas. Like Wars on Terror or world-wide daisy-chains of military bases. An independent Scotland, or Vermont, is unlikely to invade Iraq. It takes a big country to do truly insane things.

A Lesson for American States

When Americans indulge in thought experiments about the possible secession of American states, it is often assumed that most US states are too small “to go it alone.” Indeed, most Americans greatly underestimate the size of many American states in relation to numerous independent and prosperous existing nation-states.

Were Scotland a US state, for example, it would be only a medium-sized state, with a GDP smaller than the gross state products of both Missouri and Connecticut, making it about the 25th largest state in terms of GDP. Population-wise, Scotland is about equal to Minnesota and Colorado (I have removed China and the US combined economy from this graph to improve scale):

In this map, I’ve compared American states to foreign countries of similar GDP:

For more similar maps, see here.

Moreover, few Americans appreciate how enormous some American states are, especially the largest four states: California, Texas, New York, and Florida.

[RELATED: Which States Rely Most on Federal Spending]

In terms of both population and GDP, California is about equal to Canada — and with much better weather. Texas is equal in economy and population size to Australia. Pennsylvania’s economy is similar in size to Switzerland.

While secession of American states is often dismissed as absurd, there are few reasons to believe that a state like Texas — to name just one example —could not immediately transition from state to nation-state. With a large economy, port cities, oil, and easy access to European, Latin American, and even Asian economies by sea, economics arguments against such a separation fall flat. And of course, the success of smaller states like Norway, Denmark, and Switzerland illustrate that bigness is truly unnecessary. Naturally, many other states even beyond the biggest states — such as Pennsylvania, New Jersey, North Carolina and others — could do the same. These states would all be among the largest economies on earth were they to leave the US.

“But what about national defense!” some may argue. “Wouldn’t Texas be constantly at war with the United States?” Experience suggests that Texas would be at war with the United States about as frequently as Canada has been at war with the United States: zero times since 1815.

International wars rarely erupt between countries with common languages, common histories, and common economic interests. Should Scotland secede, the UK won’t be sending in the tanks, and Scotland could easily join the realm of independent nation states, just as many American states could do the same.

************

ER recommends other articles by The Mises Institute

About the author

Ryan W. McMaken is the editor of Mises Daily and The Austrian. (He accepts your article submissions. Read this first.) He has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado, and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.